[ad_1]

In 2021 an unconventional pair of collaborators embarked on a daring experiment. For two decades Steven Rayan, a mathematician and mathematical physicist, and Jeff Presslaff, a freelance composer, pianist and trombonist, geared up to remedy a person large question: Could they translate a mathematical physics investigate paper specifically into new music? Furthermore, would their musical generation audio great?

In September Rayan and Presslaff unveiled their brainchild, “Math + Jazz: Seems from a Quantum Foreseeable future.” Exactly two decades to the day that Rayan, a researcher at the College of Saskatchewan, and Presslaff, who’s based in Winnipeg, Canada, initial connected above e-mail, they gathered a 15-piece “hyperbolic band” of musicians to carry out the 5-part concert at the College of Saskatchewan. Just about every portion corresponded to a part of Rayan’s study post.

Part musical general performance and element lecture, the live performance was played to “a packed dwelling,” Rayan suggests. The lecture part dissected the paper’s scientific ideas and illustrated how people strategies had been transmogrified into music. Some of the illustrations have been literal: the slideshow highlighted hyperbolic art developed by Elliot Kienzle.

Pulling off the live performance was no straightforward feat. Due to the fact several of the musicians weren’t local, the band hadn’t rehearsed the audio with each other in man or woman right until the night in advance of the live performance, Rayan notes.

Hyperbolic Band Theory

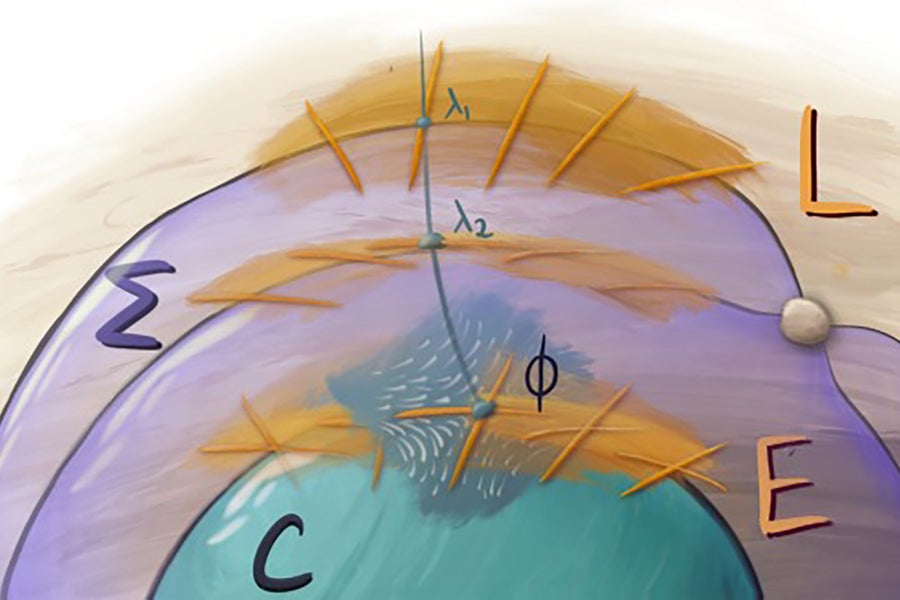

The music was based mostly on Rayan’s 2021 Science Developments write-up “Hyperbolic band concept,” which he wrote with Joseph Maciejko of the College of Alberta. Their goal was to examine whether or not band theory—which researchers use to look at the electricity concentrations of elements and the atoms that they are designed of—could be reformulated to demonstrate hyperbolic resources, which have irregular, warped preparations.

In band concept a material’s electricity ranges are thought of as remaining contained in sheetlike bands hovering over the components they belong to. These shadowy bands characterize the material’s quantum homes, and interactions involving these bands have implications for the material’s behavior.

Rayan and Maciejko succeeded in exploring a band theory that will work in the wonky earth of hyperbolic geometry, a strange geometrical realm that breaks Euclid’s “parallel postulate.” Also referred to as Euclid’s fifth postulate, this rule tells us the next: Suppose you’re provided a line. For any level that is not on that line, there will be only a person line that equally goes via that level and is parallel to the original line. In hyperbolic land, a bare minimum of two lines will go as a result of the level although also becoming parallel to the supplied line.

The exploration “is a full new method to planning materials—especially quantum materials—by re-engineering their geometry from the within out,” Rayan suggests. The method includes altering the material’s band framework to generate the wanted changes in the material’s qualities. “They can get on unconventional, exotic geometries,” he says.

This could possibly seem like, for instance, covering a curved area by tiling it with octagons so that there are not any gaps between the designs, which are nonoverlapping. To human eyes, the edges of these octagons look curved, and the shapes glimpse like they are distinct sizes, Rayan notes. But “if you experienced a distinctive kind of eye that sees the world in a hyperbolic way—maybe insectlike compound eyes—[the octagons] may well all seem the identical to you,” he claims.

The operate received a large amount of awareness from other scientists. “I’m quite amazed by the relationship involving materials science and algebraic geometry which was unearthed by the authors of this paper,” suggests Michael Groechenig, a mathematician at the University of Toronto, who wasn’t involved with the post.

Rayan is enthusiastic to use his results to learning strange elements with the likely for “disruptive programs,” such as in quantum computing. “It’s instead pleasant to see another person show an vital application of these solutions of these types of a concrete nature,” Groechenig states. The paper is “an invitation for us pure math individuals to leave our comfort and ease zone a tiny and to discover hitherto uncharted territory,” he provides.

Translating to Songs

Developing a mathematical live performance is its own sort of disruptive software of the investigate. “I didn’t want [the music] to be impressionistic,” Presslaff says. “I wished it to be genuinely genuine to arithmetic…. I have just seen far too many cross-disciplinarity jobs that just strike me as superficial. The science facet may possibly be demanding, and the art facet is pretty not demanding.”

Rayan agreed with that goal. “I had a determination to not just developing music that was someway loosely motivated by the math and the science but instead in some way retelling the mathematics phrase for phrase, equation for equation, in a musical variety,” he claims.

But embracing that obstacle also necessary that each experts go away their convenience zones and discover concepts from just about every other’s parts of abilities. Presslaff immersed himself in subjects from linear algebra and topology that served illuminate the interior workings of the study paper. Rayan dove into “trying to recognize, as a great deal as doable, the state-of-the-art musical thoughts [Presslaff] brought to the desk.”

The pair exchanged tips for roughly 18 months ahead of Presslaff even commenced crafting the music. “It’s wonderful that I by no means met Jeff in individual until finally the day in advance of the functionality on September 20,” Rayan suggests. “It was all on Zoom due to the fact of the pandemic and because of length. It was a interesting way of working—that we could achieve this even by way of purely digital implies.”

Double Fugues and Infinite Styles

It’s challenging to pinpoint whether Rayan and Presslaff achieved their grand goal: to change the primary thoughts from Rayan’s paper right into jazz tunes. Not like in mathematics analysis, there is no “proof” that they achieved their objectives. Even now, the duo is delighted with their end result. “Getting it completed was just in no way a certain factor until eventually even, say, 6 months prior to the general performance,” Rayan claims.

Hyperbolic Band performer Shah Sadikov, a Baltimore-centered violist, suggests a highlight of the concert was when Presslaff utilized a double fugue, a musical method which is “very hard to put into action,” to represent the procedure of developing an “infinite form,” Sadikov suggests. Mathematically, that intended producing an object with “no commencing, no stop,” Sadikov states. Musically, producing a double fugue involves making “one plan the basis of the musical piece and then you get the correct very same plan [and] you place it a little bit afterwards on top of it,” and so on, he states. “You generate these levels of suggestions. And then you can use counter suggestions to that, possibly getting the identical musical plan [and] placing it backwards or upwards,” he notes.

For Rayan, a highlight was hearing Presslaff’s musical just take on “the so-called particle-wave duality or the situation-momentum duality in hyperbolic band concept.” In that context, momentums can just take on a lot more proportions than positions can. “We wanted to seize in the songs the jump from, say, two dimensions to four dimensions in the most basic of these components, which are primarily based on octagonal hyperbolic lattices,” Rayan suggests.

“Hearing [Presslaff’s] attempts at introducing more voices in the new music that seize the more degrees of freedom, the unexpected jump to two additional proportions, was a relocating experience for me,” Rayan claims. “I cherished observing the audience consider to hear those additional voices just after [his] rationalization of them.”

The live performance involved one particular other creative ingredient: Kienzle’s hand-drawn illustrations. Now a graduate university student at the University of California, Berkeley, Kienzle designed the mathematical artwork for a connected investigation project that he and Rayan worked on while he was an undergraduate pupil at the College of Maryland, University Park. “This was an attempt to notify the tale by way of a visible lens,” Rayan suggests. In the concert all those illustrations served enrich the musical and verbal explanations of the math and science.

Rayan sees reinterpreting this get the job done as a result of musical and artistic lenses as a way of bringing it total circle. Substantially of the mathematical and scientific concepts featured in his papers borrow ideas from the entire world of art. For occasion, “hyperbolic tilings are quite reminiscent of” Dutch graphic artist M. C. Escher’s legendary woodcuts, he notes. Rayan strategies to carry on discovering new strategies of fusing mathematical and artistic views to “give back to art” while also sprouting new insights for his analysis.

[ad_2]

Source hyperlink