[ad_1]

Some 14,000 a long time back, downtown Los Angeles was awash with dire wolves, saber-toothed cats, approximately 1-ton camels and 10-foot-lengthy floor sloths. But in the geologic blink of an eye, almost everything improved. By just after 13,000 yrs in the past, these large animals had all disappeared. What had been once lush woodlands experienced come to be a dry, shrubby landscape named a chaparral, and huge fires were being prevalent. What went mistaken?

Attainable answers to that query appear from new investigation into the famed La Brea Tar Pits printed on August 17 in Science. Between 50,000 and 10,000 many years ago, naturally occurring asphalt in these “tar pits” trapped organisms ranging from significant predators to hoary bats (Lasiurus cinereus), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis). The new examine reveals just how swiftly the greatest animals disappeared from the La Brea fossil record.

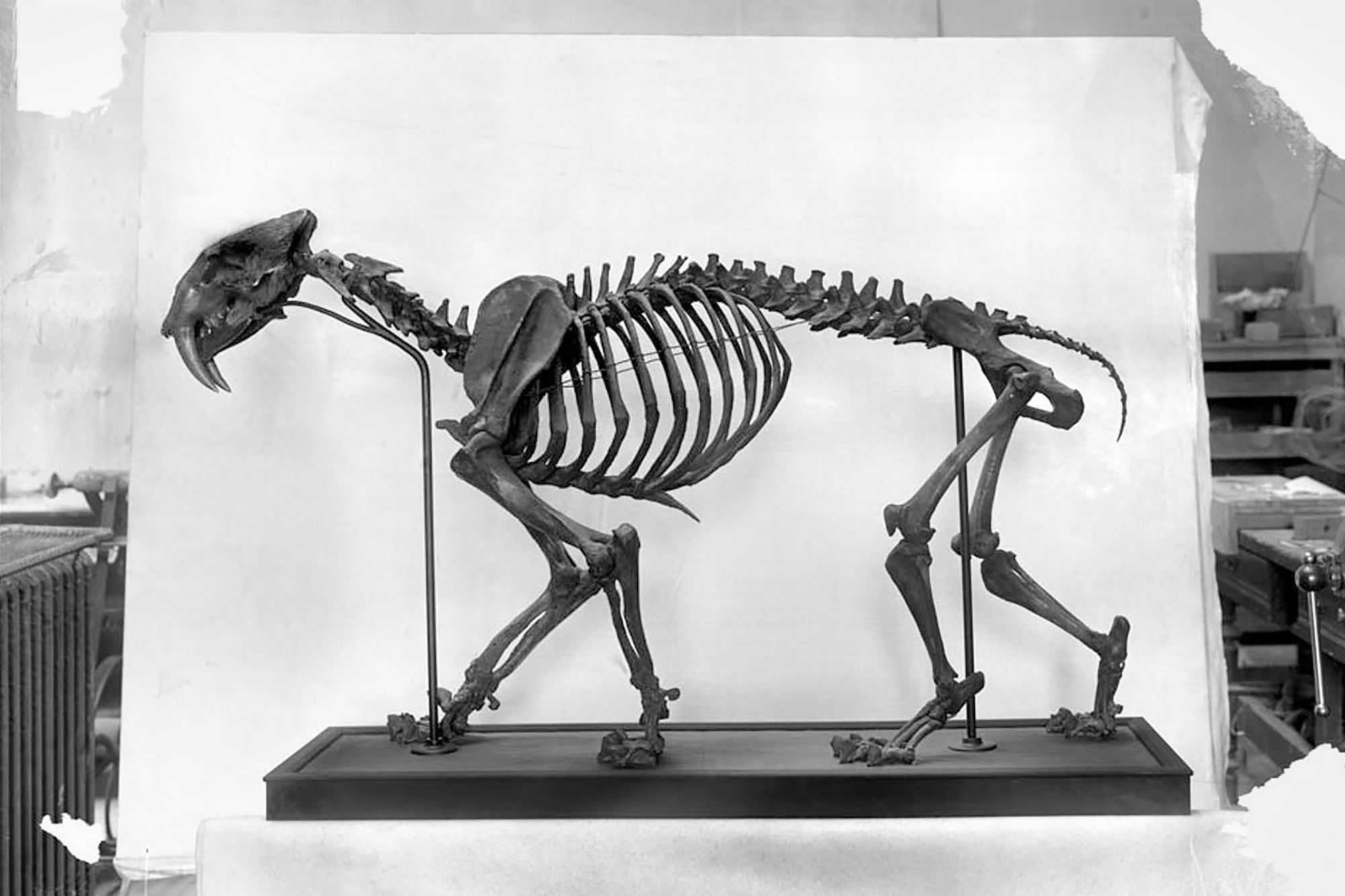

The scientists dated 172 specimens belonging to 7 extinct species—the dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus), the historic bison (Bison antiquus), a camel called Camelops hesternus, a horse referred to as Equus occidentalis, the saber-toothed cat (Smilodon fatalis), the American lion (Panthera atrox) and Harlan’s ground sloth (Paramylodon harlani)—and the nonetheless-dwelling coyote (Canis latrans). The experts seen that whilst the coyote fossils dated anyplace from 16,000 to 10,000 a long time back, each and every other species abruptly disappeared someday among 14,000 and 13,000 years in the past, with the camels and sloths seemingly blinking out a couple hundred years in advance of the predators.

“No just one in the examine was geared up for what we discovered,” suggests F. Robin O’Keefe, a biologist at Marshall University and a co-creator of the new investigate. “The coyotes continue to keep becoming deposited, but the megafauna just, poof, vanish. And for most of them it is like a ‘poof’—it’s a quite spectacular event.”

To check out to fully grasp the destiny of these mammals, O’Keefe and his colleagues analyzed sediment cores from a close by lake that delivered data on air temperature, salinity and precipitation. The scientists have been particularly struck by a 300-year-very long period of time of high charcoal accumulation from wildfires in the lake that commenced about 13,200 many years ago—right all over when the megafauna went missing from the tar pits. “We see these big pulses of charcoal heading into Lake Elsinore all of a sudden, and they are great, when compared to anything that occurs prior to that time or just after that time,” O’Keefe states. “That’s what clued us in to ‘Okay, the fires are a definitely important factor.’”

Following the scientists applied a personal computer model to figure out how fires, weather modify, species loss and human arrival in the spot suit jointly. And the consequence is a significantly a lot more intricate picture of the extinction than that depicted by prior theories, which normally blame the extinctions on just 1 offender, this sort of as human hunting or weather alter. As a substitute, O’Keefe claims, individuals most likely pushed the ecosystem in excess of the brink by killing off herbivores, which allowed the vegetation that served as wildfire gas to proliferate just as the climate was drying out in any case and remaining carnivores with out prey.

“It’s not necessarily like substantial wildfires drove an extinction of megafauna,” says Allison Karp, a paleoecologist at Yale College, who was not included in the new exploration. “It’s that human dynamics changed the fireplace routine this interacted with a weather that is arid and at a larger temperature and this, put together with decreases in herbivore densities, truly pushed the system in a nonlinear way and shifted it to a further state—a state that provided a large amount fewer herbivores and a incredibly distinctive vegetation group and a considerably higher fire regime than experienced been found previously.”

Jacquelyn Gill, a paleoecologist at the College of Maine, who was also not associated in the new work, was not surprised that O’Keefe’s crew identified this sort of a nuanced explanation. “We know that in modern-day systems, extinction is pretty not often unicausal,” Gill suggests. “You normally will need to have some force that is stressing this populace. Then there is typically an element of lousy luck or some other stressor that comes in. We see that over and over all over again.”

O’Keefe, Karp and Gill concur that the parallels amongst today’s headlines and the disappearance of these legendary animals from southern California towards a backdrop of wildfires and local climate alter are eerie.

O’Keefe notes that the analysis traces a change from two unique ecosystems in just a couple of hundreds of years. “Mathematically, it’s a catastrophe,” he claims. “If the medium of that condition shift is fireplace, and then you seem around, and everything’s commencing to catch on fire, you start to believe, ‘Is it taking place once again?’ Which is a rational issue to imagine.”

Knowledge how extinctions unfolded prolonged ago, Gill claims, can also assist ecologists far better forecast what might come about subsequent nowadays. In that way, they can forecast which species, if still left to their personal units, are much more probable to go the way of the dire wolves or that of the coyotes. “Ecologically talking, there are winners and losers when we have these significant upheaval activities,” Gill claims. “That data can help us to carry out the vital triage that we will need to do as we try to save a million species.”

[ad_2]

Supply connection