[ad_1]

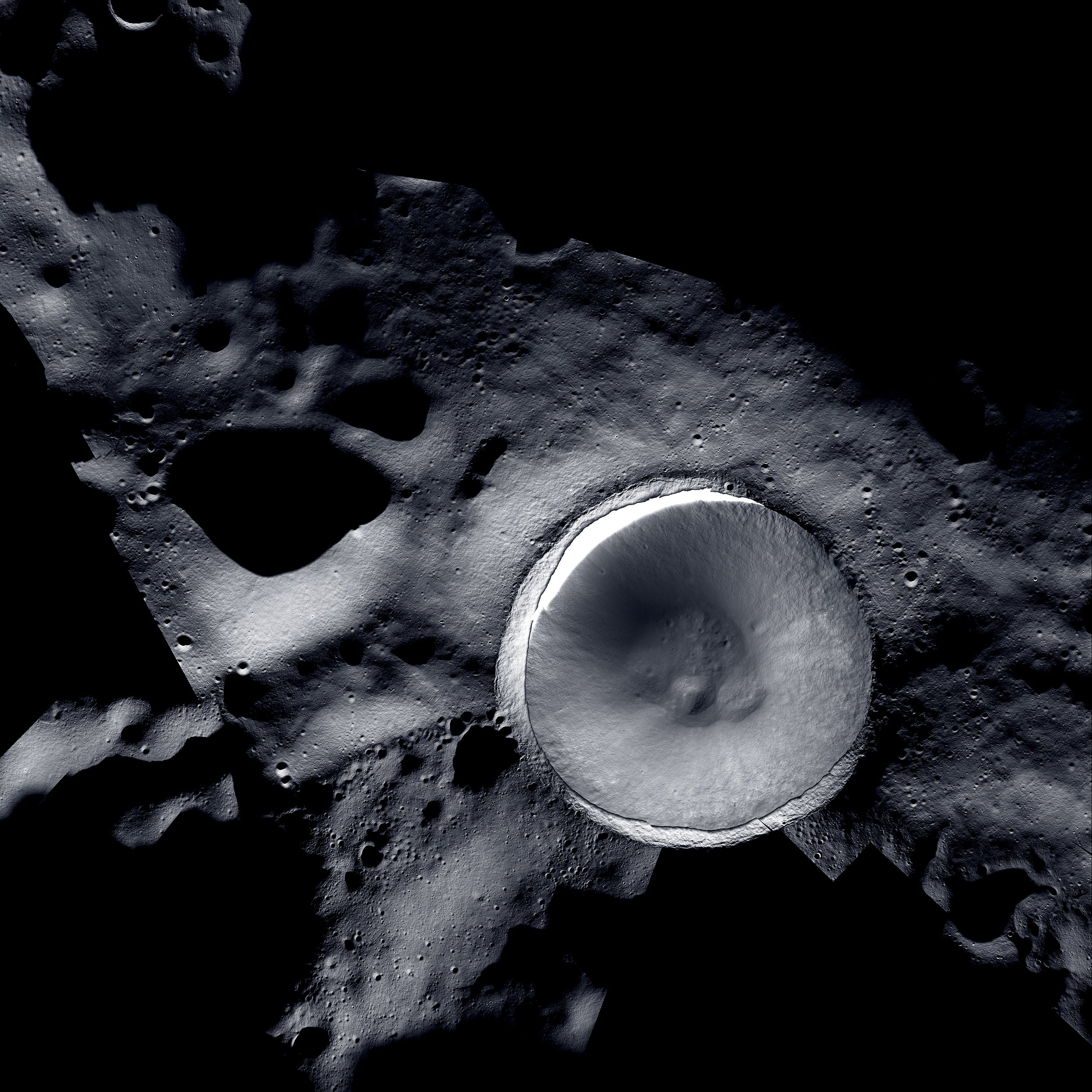

Shackleton Crater pops from the moon’s South Pole, as if a spherical cookie cutter have been just punched into the rocks, in a lovely new graphic that demonstrates parts of the lunar floor that are permanently shrouded by shadow.

The crater gapes at about 13 miles large and 2.6 miles deep. Its inside and walls are completely shadowed—they never obtain direct sunlight—because of the moon’s slight 1.5-diploma tilt on its axis. (For comparison, Earth is tilted at about 23.5 levels.) That can make it challenging to peer into the crater, which is suspected to hold ice deposits. Some peaks together its rim, which glisten white in the recently snapped graphic, acquire daylight for a great deal of the year.

To build an graphic with a crystal apparent check out of the crater bottom, NASA researchers combined details from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Digicam (LROC), an imaging system on the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has been orbiting the moon considering that 2009, and ShadowCam, a NASA instrument onboard Danuri, a Korean spacecraft that released in 2022.

These two instruments are complementary. LROC captures significant-resolution visuals on the sunlit regions of the moon’s floor but just can’t generate good imagery in lower mild. ShadowCam is intended to use mirrored, instead than immediate, sunlight to produce in-depth pics of completely shadowed places, but it delivers washed-out photographs of any space lit by direct daylight.

Combining the two yields mosaics, these kinds of as the new just one of the Shackleton Crater. In this image, the visuals of the crater flooring and partitions count on details from ShadowCam, whilst the rim and spots outside the house the crater arrive courtesy of LROC.

Since its launch, ShadowCam has also offered peeks into other lunar craters and discovered if not-invisible capabilities, these types of as an apparent landslide in just Spudis Crater. The lunar South Pole is intriguing, in accordance to NASA, for the reason that conditions are so cold and dark in these regions that they may possibly host drinking water ice or other frozen volatiles beneath the area. Observations taken by an orbiting spacecraft in the 1990s suggested a large amount of hydrogen in the subsurface of some of the lunar South Pole’s craters, a possible sign of h2o ice. A peak in close proximity to Shackleton Crater is among the proposed landing web pages for the Artemis III mission, a NASA effort to send out human crews to the lunar surface. If astronauts can extract oxygen and hydrogen from frozen ice deposits in just the lunar surface area, they may perhaps be ready to use those people assets for gas and existence aid, which would help more time stays on the moon in the long term.

[ad_2]

Resource connection