[ad_1]

November 28, 2023

3 min read

Microbes tear up plastic into teeny little parts that are even more hazardous to ecosystems

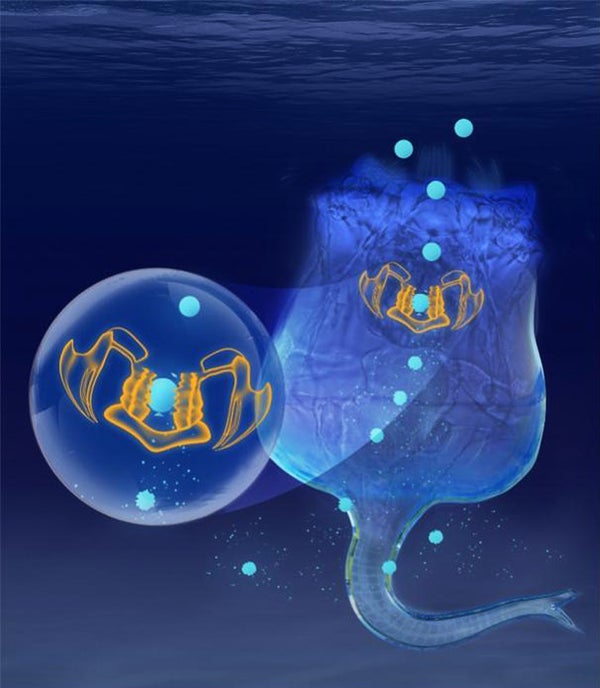

The rotifer’s masticatory equipment (in yellow) is robust ample to fracture grind out far more than 300,000 nanoplastic particles each and every day.

Little creatures are gnawing absent at plastic we people are pouring into the surroundings, creating the air pollution considerably less visible but potentially additional problematic than at any time, according to new exploration.

In that function, posted on November 9 in Nature Nanotechnology, scientists fed compact parts of fluorescent plastic to plankton identified as rotifers and viewed to see what transpired. Their observations and analysis counsel that in just a single working day, a person of these tiny animals in a plastic-loaded setting can make a lot more than 300,000 particles of nanoplastic that are smaller sized than a single micron across—a fraction of the size of a human purple blood cell.

Nanoplastic is a important worry inside of the larger sized problem of microplastics, which protect a broad selection of dimensions, from one micron to five millimeters. Nanoplastics’ even smaller measurement could make them especially harmful to individuals and the environment because they can a lot more conveniently get into the bloodstream and deep into the lungs. They can also be ingested by tiny animals and develop into concentrated up the food chain. The new study—which complements a expanding overall body of exploration showing that plastic pollution extends from the deepest ocean trenches into the environment—sheds mild on how astoundingly rapidly plastic can proliferate.

“We know that microplastics finally grow to be nanoplastics, but you do not assume it’s heading to happen that quick,” claims Jacqueline Padilla-Gamiño, a maritime biologist at the College of Washington, who was not concerned in the new research. Other purely natural forces, most notably daylight, also crack plastic into progressively more compact parts but act extra slowly but surely.

The scientists at the rear of the new investigate were being influenced by a 2018 examine that showed that Antarctic krill could split microplastics into nanoplastics. Individuals animals dwell in incredibly cold—and fewer polluted—environments, however. The scientists guiding the new function wished to fully grasp irrespective of whether the same phenomenon also played out in animals that lived in warmer, additional plastic-stuffed waters, says analyze co-author Baoshan Xing, an environmental and soil scientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

From there, rotifers were an noticeable choice mainly because they are common and outfitted with what researchers connect with trophi—specialized grinders to system their food plan of algae and other little bites. “Rotifers have this exclusive chewing equipment, like teeth,” Xing suggests.

Xing and his colleagues located that several rotifer species do indeed split down microplastic. Some experiments have advised specified microbes and enzymes can digest plastic by breaking aside the very molecules that it is manufactured of, chemically shifting them into benign compounds and reducing the sum of plastic in the environment. But the researchers found a unique, much less optimistic end result: the rotifers just fragmented the plastic by building scratch marks on the plastic bits and creating ever more compact pieces. The scientists tested distinct types of plastic, as very well as plastic weakened by publicity to gentle, and all ended up susceptible to the rotifers’ trophi.

Xing states it’s not likely that rotifers are by itself in their staggering ability to tear aside microplastic. “We assume any organisms with that type of chewing equipment likely will have a identical approach,” he suggests. He and his colleagues want to perform comparable investigations applying additional species, particularly animals that stay in soil relatively than water, to realize how the phenomenon could be playing out in a wider selection of ecosystems.

The new study, Padilla-Gamiño suggests, is an vital action towards knowing what occurs to plastic more than its lengthy lifetime of up to hundreds of years in the atmosphere. “We have manufactured massive developments into [understanding] how significantly plastic there is, but there’s still a large amount of controversy about the various pathways that plastics consider,” she suggests. “I consider this is a really interesting study highlighting 1 of these pathways.”

And it is also a reminder not to forget about the small, unusual kinds of life that we share our world with. “It’s incredible how these minimal creatures have this sort of incredible power,” Padilla-Gamiño says.

[ad_2]

Supply url